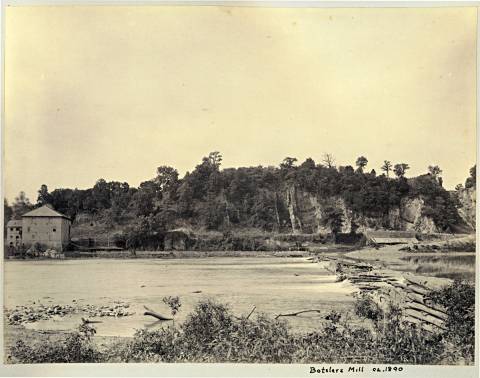

In 1827, the steady rush of the Potomac powered a new enterprise just below Shepherdstown. There, at the crossing of Pack Horse Ford, Dr. Henry Boteler and his partner, George F. Reynolds, constructed a grist mill they named Potomac Mill. This enterprise quickly found success and soon became yet another familiar sign of industry along the riverbanks in Eastern Jefferson County.

Boteler's ambitions reached beyond simply grinding grain. Word spread that the newly chartered Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company was searching for a source of “hydraulic cement” and "water lime" for use in the construction of their large infrastructure project. Recognizing the great opportunity that awaited him, Boteler wrote President Charles Fenton Mercer of the C. & O. Canal on January 14, 1828, boasting that he owned an abundant supply of stone close to his mill that would be applicable to their purposes.

Intrigued by Boteler's claims, Mercer responded almost immediately, requesting samples of the stone deposits. Boteler eagerly fulfilled Mercer's requests, sending samples and the following notes regarding his stone supply.

“The water lime: one in its natural state, one burnt, and the powder after being calcined. This stone is found in great abundance on my premises, immediately on the bank of the Potomac River, one mile below this place. It is found on the surface and under the ground to a considerable depth. The hill, which appears to be entirely of this stone, is 200 feet high, and nearly half a mile around its base. It is of easy access, and can be quarried with more facility than the common limestone. In preparing for its use, it requires only one-third of the time allotted to the burning of lime: consequently it requires only a third of the wood necessary for calcining lime.”

Word of Boteler’s “natural cement” spread quickly. By February 11, 1828, the U.S. House of Representatives had taken notice of the discovery near Shepherdstown. It wasn’t until September that the C. & O. Canal Company confirmed what Boteler had claimed all along, that the stone near his mill was the only material along the canal line suitable for the purpose of constructing a canal. Although deposits of natural cement also existed at Round Top and Cumberland, the company had not yet discovered them.

The partners quoted the canal company a rate of 18.75 cents per bushel to burn, grind, and deliver the cement at the mill, with an estimated additional 17 to 18 cents per bushel to ship it downriver to Georgetown.

Unlike the Junto of Harpers Ferry, consisting of the Wager family and the United States government, the canal company made no effort to monopolize the freighting or production of cement. They held no financial interest in its production. The canal company was concerned only with supply meeting demand, making efforts to ensure ample quantities of cement would be available for construction.

Between 1828 and 1829, Boteler and Reynolds converted part of their successful flour mill operation into a cement works. During this transition, they constructed three large kilns. Even with part of their mill undergoing a conversion, the partners managed to produce one hundred barrels of flour a day. By September 1829, the new cement company was in full operation. To keep up with growing demand, the cement works employed fifty men, ten of whom were mechanics.

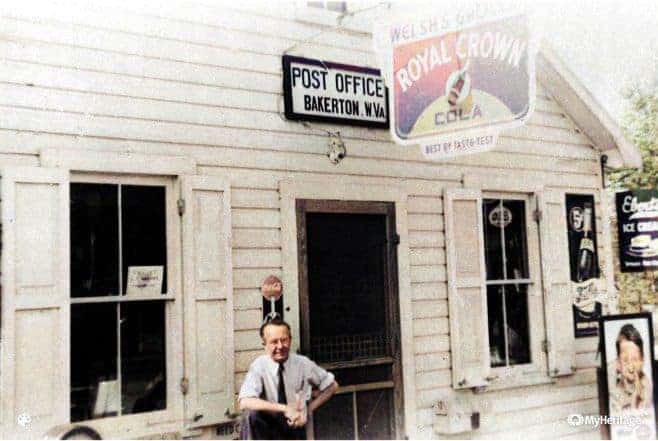

With no background in cement making or quarrying, Boteler and Reynolds quickly realized they needed skilled hands to bring their venture to life. They turned to the canal company for help, requesting that it recruit experienced quarrymen and laborers from Wales and England. The partners promised to pay what they deemed the “highest of wages”, eight to nine dollars a month, and offered to cover travel expenses for those too destitute to afford passage. If inclement weather halted work, the company pledged to board their men for free, though their wages would be reduced to reflect the lost time.

The "high wages" purported by the partners weren't necessarily generous. The average canal worker earned ten dollars per month, meaning Boteler and Reynolds were hoping to cut labor costs while still marketing the opportunity as fair employment.

The cement company received its first group of immigrants in October 1828. In a report to the canal company, Boteler and Reynolds noted that the newcomers were “civil, industrious, and satisfied with their situation,” though they admitted the men were “very awkward,” unaccustomed to the specialized tasks at hand and slow to find their footing. These first workers, numbering perhaps five to eight, were likely common laborers rather than trained quarrymen. Although the partners were skilled businessmen, they appear to have had much to learn about managing immigrant labor. Reports indicate that the company failed to provide even the most basic clothing for its laborers.

Remaining in need of skilled laborers, the partners requested eight to ten more able-bodied immigrant men under the same terms of employment. In particular, the businessmen desired 3 to 4 excellent quarrymen and 1 to 2 stonemasons. The first round of laborers recruited by the canal company likely included the families of the men. In their second request, the partners explicitly demanded that the canal company refrain from sending women and children to their works, stating that they had neither work nor accommodation for them.

The C. & O. Canal company was well aware of the discomforts and widespread impoverishment among the laborer camps on the line of the canal. Citing conditions and immigrant laborer demands, the company continued to pressure the partners to accept more women and children into their care. According to the canal company, the mill was able to provide accommodations much more habitable than elsewhere along the canal line. It is unclear what accommodations the canal company believed the cement mill could provide. There is no evidence of any worker lodging near the cement mill remains, nor is any such shelter documented in historical works.

Despite Boteler's and Reynold's demands, the canal company assigned one woman and one child to the cement mill to serve the laborers as a cook and a laundress. Boteler and Reynolds reported that the immigrants were “destitute of the comforts of life” and that they had felt the need to clothe them. To do this, they deducted the cost of clothing from the laborers' wages. Evidently content with their employment, the laborers furnished Boteler and Reynolds with the names of other Welshmen desirous of securing work at the cement mill.

Although the mill requested additional shipments of laborers, the canal company declined additional recruits for Boteler and Reynolds, arguing that the wages offered were considerably lower than those paid elsewhere in the country. However, the partners maintained that their pay rates were consistent with those of other employers in the immediate vicinity of the cement works.

It is important to note that the canal company was already having trouble with its immigrant workforce. Even after resolving the difficulties of transporting laborers from their homeland to America, and then to worksites, it was a struggle to keep the immigrants on the job. This ongoing problem was cited as another reason the company could not supply more immigrant workers to the cement mill.

Following these discussions, on April 1, 1830, Boteler and Reynolds agreed to increase wages to between ten and twelve dollars per month, depending on each laborer’s position and ability. That month, they reported employing fifty men in total, including eight skilled stonemasons engaged in the construction of new kilns.

Between September 1829 and January 1830, the C. & O. Canal Company directly hired many boatmen to transport cement from Boteler's Mill, paying wages of ⅓ cent per bushel of cement per mile. Among these boatmen, Henry Strider contracted to carry 15,000 bushels, John Strider, 40,000 bushels, Jacob Fouke, 10,000 bushels, and Joseph Hollman, 20,000 bushels. Other boatmen documented as carrying cement for the canal company were Samuel Moxley, Karns, Ridgeway, and Sinclair.

Although the cement mill owned some of the bags used for shipment, the majority were supplied by the canal company. In December 1829, cement was shipped in flour bags due to a shortage of cement bags, probably at the expense of the partnership.

To ease this shortage, on January 12, 1830, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company offered boatmen a payment of two cents per bushel if they supplied their own bags, boxes, and boat covers. This arrangement was not popular among boatmen; they expressed frustration at being required to assist in filling the bags at the cement works, arguing that they were not being paid for their time and labor.

This friction over pay and duties was only one example of the growing discontent between the canal company and its boatmen. The company accused several boatmen of violating their contracts. McFarland, an agent for the canal, reported that John and Henry Strider had stored shipments of cement at Harpers Ferry to await high water, a direct breach of contract. According to the canal company, many boatmen were deliberately choosing to ship only during low water, when carrying other freight was unprofitable.

The boatmen countered that delays at the cement mill were destroying their profits and prolonging delivery times. John Strider noted that he was held at the mill for five days waiting to be loaded.

The late winter and early spring of 1830 brought a series of setbacks for the cement mill. In February, operations were halted due to severe cold, and the workforce was temporarily dispersed. The mill closed again for two weeks in March while the tailrace was deepened; during the work, eleven laborers fell ill after prolonged exposure to the icy water. Only a week later, the Potomac River flooded, forcing yet another shutdown.

By midsummer, the partners faced a new problem. The partners were producing cement at a rate higher than the canal company could consume. In July 1830, they informed the canal company that the mill would have to cease operations by September 1 because their storage facilities were nearly full. To relieve the surplus, they requested that the canal company remove some of the cement already produced.

The same month, the canal company reported that work on the Monocacy Aqueduct had been suspended for “lack of Shepherdstown cement.” Given the mill’s considerable surplus, the shortage likely stemmed not from production issues but from continuing discord between the canal company and its boatmen, resulting in transportation and delivery complications.

By June 1831, the canal company requested that the cement mill suspend production, resulting in a temporary shutdown that lasted through part of the summer. The following spring, in April 1832, operations were again halted due to construction problems at the mill. Later that year, in November, the water level of the Potomac River dropped so low that it could no longer power the mill. Because the mill relied entirely on the river and canal for both power and transportation, these interruptions created serious strain on operations, and reports indicated that cement supplies had reached critically low levels.

Although the mill struggled with transportation issues and recurring setbacks, Potomac Mill remained the number one supplier of natural cement for the C. & O. Canal until 1837, when Round Top Mill began production.

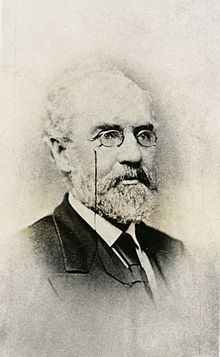

Alexander Boteler (1815-1892)

In 1835, one year before his death, Boteler sold his interest in the mill to his partner, George Reynolds. Buried by the burden of his debts, Reynolds was forced to sell the mill at auction.

Henry Boteler's 21-year-old son, Alexander, purchased both the family business and the considerable debt attached to it. A recent Princeton graduate and newlywed, Alexander assumed management of the Potomac Mill. Under his direction, the mill supplied cement to Georgetown, Baltimore, and Washington. In 1851, the mill secured a prestigious contract to furnish cement for the construction of the U.S. Capitol.

By 1859, Alexander Boteler had been elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a member of the Whig Party. His political prominence and later his active support of the Confederate cause made him a target during the Civil War. On August 19, 1861, Union troops burned the Potomac Mill to the ground.

After the war, Boteler lacked the financial means to rebuild the mill, and it was eventually sold at auction. In 1867, the Potomac Mills, Mining, and Manufacturing Company was organized under the leadership of President James W. Barber. As an officer, Barber oversaw repairs to the old mill. The details of the company’s early operations remain unclear, but by 1875 the mill was once again in a cycle of production. This time, the mill was operated under the direction of Washington D.C. builder Major Harry Woodward Blut, exclusively producing cement. Newspaper reports from that period note that all of the cement produced was shipped to Washington via the canal.

The cement company did not operate year-round, as its production and shipping were closely tied to the canal. When the canal closed each winter due to ice in the locks, the mill was forced to shut down as well. To retain enough workers during the active season, the company had to accommodate the schedules of other weather-dependent industries. This arrangement is illustrated in 1876, when Major Blut temporarily halted operations in June so his laborers could assist local farmers with the harvest.

On May 17, 1879, the Shepherdstown register published:

“The Potomac Cement Mills below town, are now running regularly, though not to their full capacity. The daily average is about seventy-five barrels. Some twenty or twenty-five hands are kept in constant employment under the management of Mr. J. E. Lucas, the efficient Superintendent. There has recently been put up in the mills a set of new and improved buhr for grinding cement, which are said to be superior to the old style of buhr. We noticed the other day, about one thousand barrels of cement ready for market; about seven hundred of that number has been shipped on the boat of Mr. J.W. Osbourn via the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal to Washington. The cement is now considered the best in the country and the demand for it is rapidly increasing. The five kilns are constantly burning, and the business of the mill has necessitated the building of a new packing machine, which is now being made by that expert old millwright, Mr. Davy Karns, of Williamsport, MD.”

Despite the seasonal interruptions and the need to share labor with local farms and industry, the mill continued to recover. By December 1879, the company returned to operating at full capacity. The 1881 season brought new leadership under Superintendent John W. Magaha, who oversaw a crew of twenty-six men. That April, boatman George W. Knode shipped the first load of cement to Washington. Magaha hoped to maintain steady, year-round production, but familiar challenges soon returned. Two floods and a break in the dam left the water level too low to power the mill, forcing operations to cease once more by mid-November.

The mill’s reliance on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal and the Potomac River left it vulnerable to recurring disruptions from droughts, floods, and canal closures. Falling demand, driven in part by the rising popularity of Portland cement, further contributed to the mill’s struggles. In 1900, Major Blut undertook significant repairs and improvements in preparation for the 1901 season. Unfortunately, his death in January 1901 left the mill shuttered.